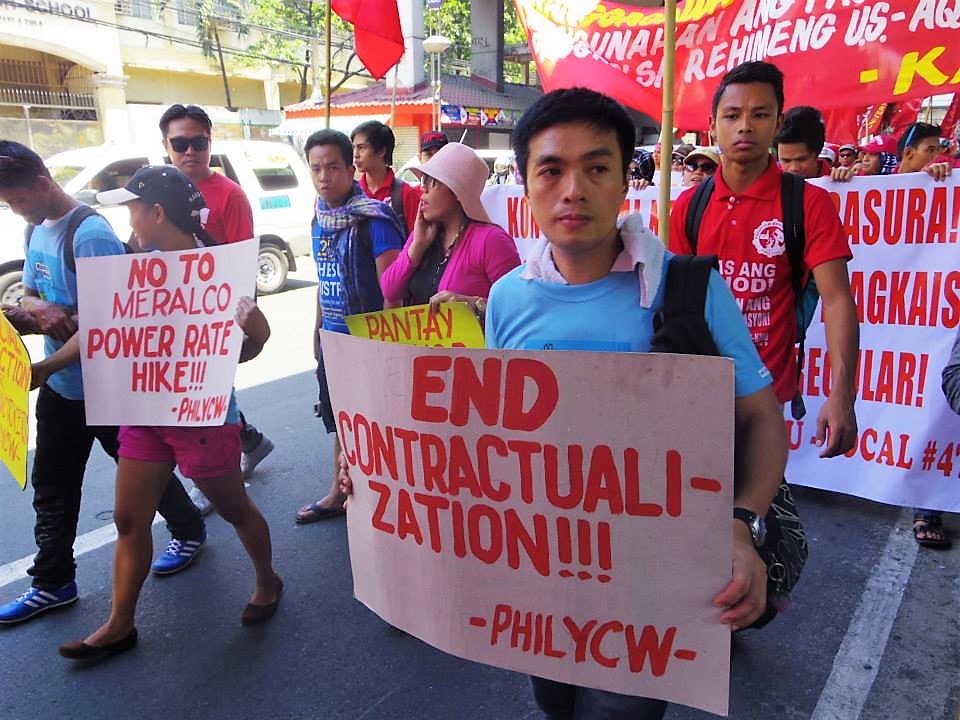

My name is George Verzosa, I come from Calbayog City (Southern part of the Philippines). I have never completed my college education because my parents could not afford to send me and my siblings to school. I migrated to Manila to find work and I worked in a sack factory as a machine operator under a contractual agency. I worked with the minimum salary, while some of my co-workers were below the minimum wage. When I had overtime hours and received extra pay, I sent it to my relatives and family way back in my province.

We were required to work rapidly because we had a “quota” to achieve and they wanted surplus production. When we did not meet the quota required for the day, it was deducted from our salary. However, when we exceeded the production quota, there was no compensation.

In 2014, my work became more precarious. I worked only three to four days a week. It was a “no work, no pay” policy, so the days I had no work, I had no income. It was extremely difficult for me to help my family and even to support my own needs, I was renting an apartment too.

Working in Saudi Arabia

This situation forced me to decide to work abroad. I looked for an agency and I was assigned to work in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA). I was requested to submit to many requirements which were costly, including the processing and placement fees. I read the contract and it looked fine, so I signed it. When I arrived there, I worked in a restaurant as a baker and a chicken griller. After two months, I really got frustrated. The contract I had signed was not fulfilled. They didn’t give me the basic salary as stated in the contract, no overtime pay, no day-offs and my working hours were excessively long.

Because I learned from the YCW to stand up for my rights and to adhere to the basic human principles, I talked with my colleagues about the contract we had signed. Then we decided to speak together with our Arab employer. His only response was that the contract had been signed in the Philippines not in KSA. Only when you got sick and were at the hospital, that was considered as a day-off. The overtime pay was already included in the monthly salary. He asked us to immediately return to our working area and threatened to cut our salaries if we didn’t work properly.

A few months later, we were moved to another branch of the restaurant. There I talked again with my new employer about issues related to wages, day-offs and overtime. They created false allegations against me. A few days later they asked me to pack my things and I was deported back to the Philippines without getting my one and a half months' salary. It was unexpected, I was not ready to leave that day and I had no choice but to leave my personal belongings.

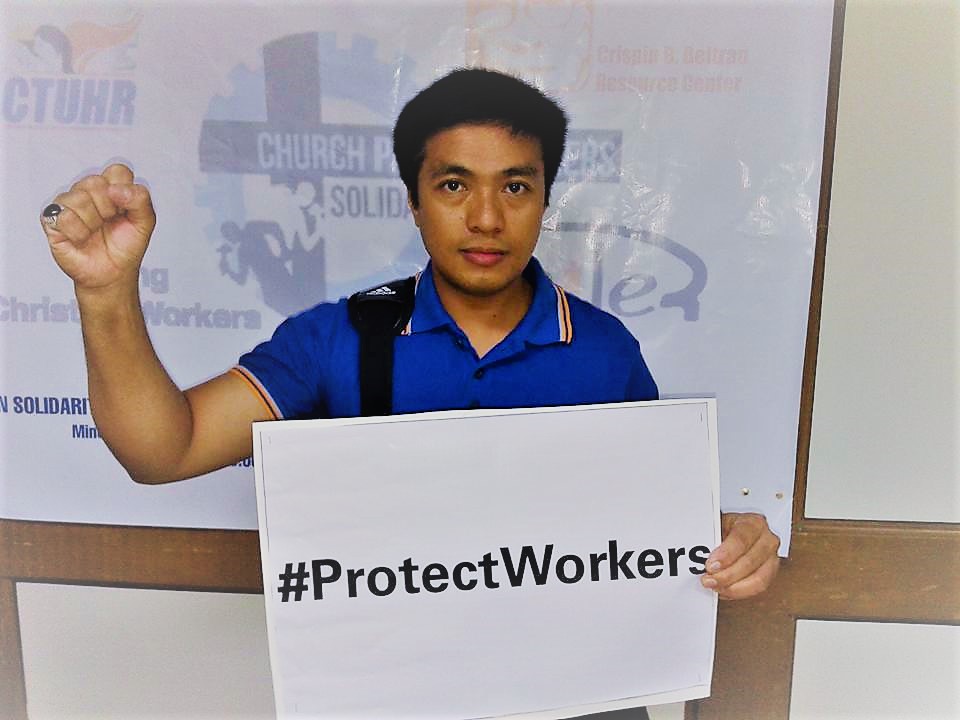

Fighting for my Rights Back in the Philippines

When I arrived back in the Philippines, I met the agency and discussed with them about what had happened. The agency argued that it could not do anything and could not continue with the signed working contract.

The YCW assisted me to go to the Philippine Overseas Employment Agency (POEA) to consult about what had happened to me. They summoned the agency and we had three hearings on the case. During the 2nd and 3rd hearings they tried to bring me to accept 50,000 pesos (1,000 euros) but I did not agree.

The case was transferred to the National Labor Relationship Commission (NLRC) upon the recommendations of the conciliator. We were supported by Atty. Maravilla, the Philippine YCW supporter and legal adviser. And we had four hearings.

We received notice of the decision in 2016, informing that I had won the case against the agency. They are being fined around 300,000 pesos (6,500 euros) to pay my compensation.

Working abroad is a hard choice, but we are left with no option. There is a lack of employment in the Philippines and statistically around 3,500 Filipinos are leaving the country every day to find work abroad. It is then the duty of the state to provide and create jobs within the country or if it is not the case, to protect its citizens who are working abroad

English

English  Español

Español  Français

Français