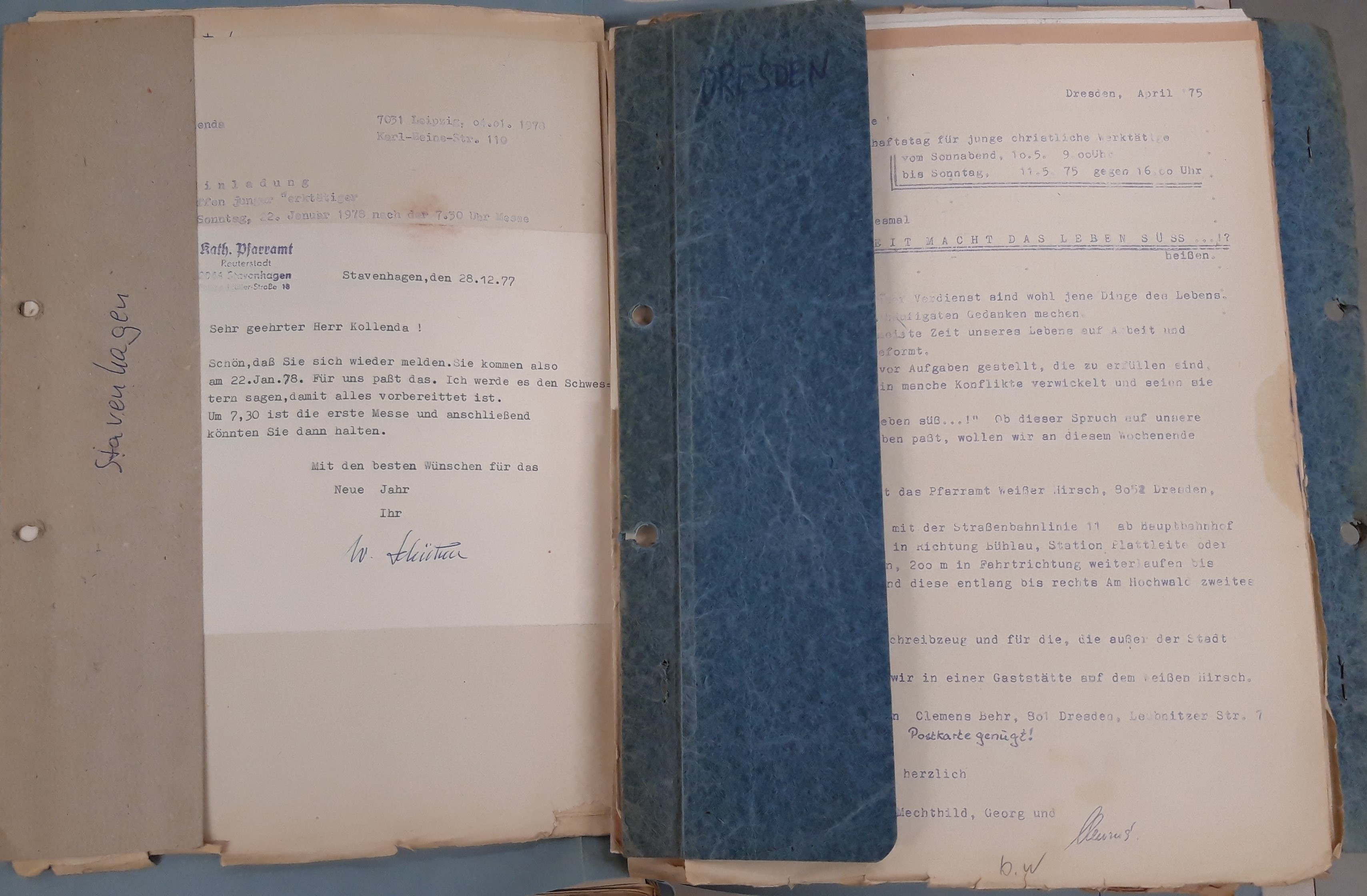

The files concerning the YCW in the German Democratic Republic are now safely stored at KADOC

We all know the images of Germans wielding hammers and chisels, hacking away at the wall that had kept them separated from each other. 32 years ago to this day, on the 9th November of November 1989, the Berlin wall fell. Not only did it end the partition of Berlin, it also set in motion the crumbling of the Eastern Bloc and signified the end of the Cold War that had divided Europe and the world for the previous four decades. The historical significance of this day can hardly be exaggerated.

Hence, today is an excellent occasion to talk about an intriguing find in the IYCW archives. Among the numerous boxes containing country files, we came across two boxes that had ‘Eastern-Germany’ written on them. The boxes are filled with handwritten papers, often lists of members or very concise reports. What was the story of these documents? Was there a YCW in the German Democratic Republic? And, if so, how did the archive boxes make it safely to Brussels?

With the help of the German CAJ and Bernhard Bormann, we were able to contact Norbert Kollenda (°1941), who knows everything about this intriguing piece of archive. He was the only full-time leader of the Junge Christlichen Werktätigen in the German Democratic Republic from 1970-1981. From 1969 onwards, Norbert was asked by the IYCW to explore the possibilities of expanding the YCW into other socialist countries such as Czechoslovakia and Poland. When we contacted him he was very eager to answer our questions. We thank him very much for the following short interview.

Norbert Kollenda, the only full time responsible of the Jünge Christliche Werktätige

S: Can you tell us what the JCW looked like in the GDR? How did it adapt to life under the regime and how did it eventually become banned?

N: With the exception of two smaller regions, the GDR was a diaspora. In 1970, for example, 10% of all newborns in Leipzig were baptized. The pastors tried to ensure that we did not woo the youngsters away. In addition, there were hardly any young apprentices or workers in the parishes - and this also applied to the Protestant congregations. Although believers were generally denied the opportunity to graduate from high school later on to study, we mostly met schoolchildren and students in the congregations. (Merkel, as a pastor's daughter, was also able to study!) We were able to form small groups in various places through contacts in the congregations, priests, word of mouth, summer camps, and weekends in church youth centers. We also tried to be active in metropolitan areas. The young people met regularly at home to work according to the methods of the CAJ. It was clear to us that we were being targeted by the Stasi and, on the other hand, that most of the bishops did not like us.

Initially, even if the Catholic Church in the GDR was a staunch opponent of the regime, it did make arrangements with it behind the scenes. The state and the state security service of the GDR served the church to discipline unpleasant theologians and groups. They - that is, a monsignor - always invoked secret negotiations with the state. It even went so far that a solidarity group was banned with the help of the Stasi. The GDR bishops' conference banned the JCW in 1980 - in a "diplomatic" description, of course.

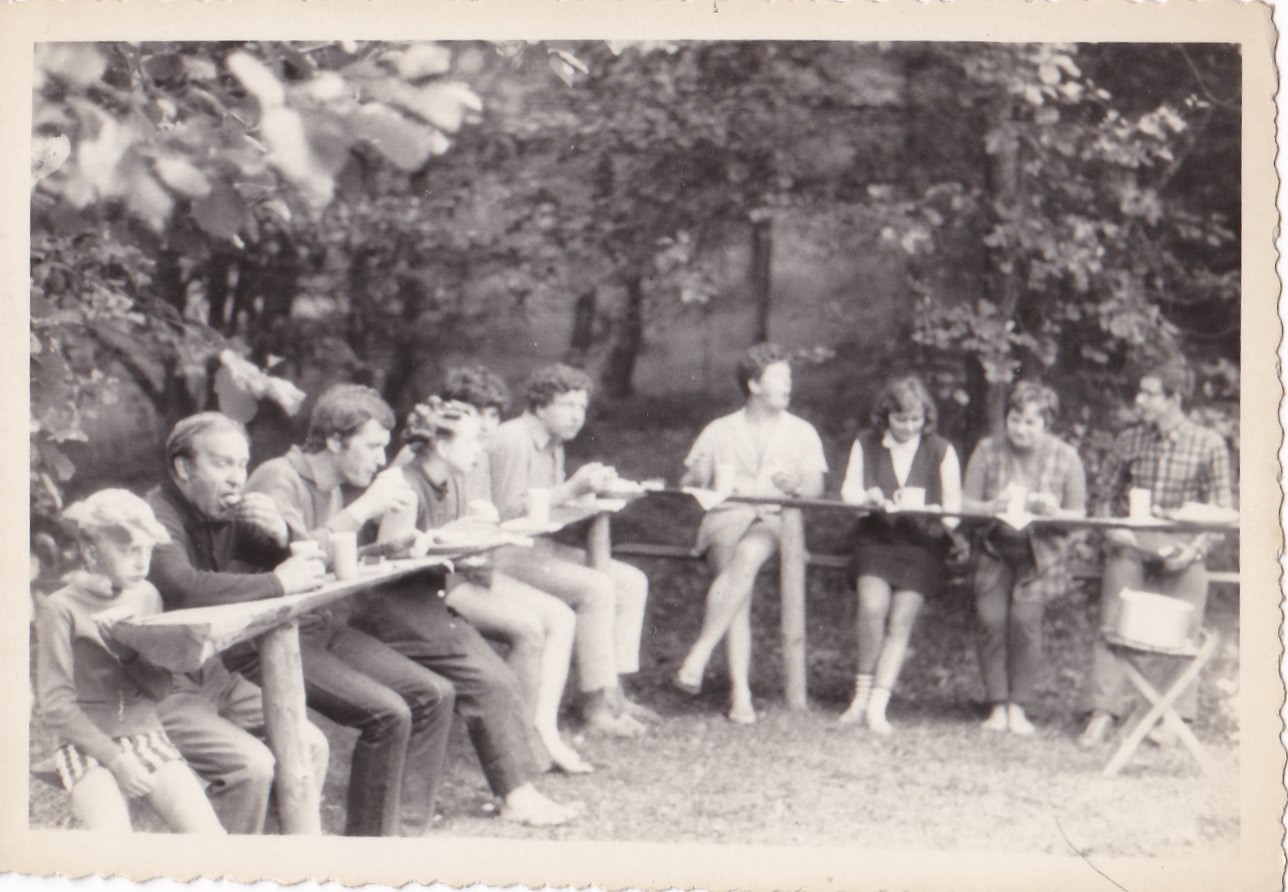

Summer camp in 1979, Norbert on the right

S: While processing the IYCW archive in KADOC, I came across two archive boxes from the GDR. Can you tell me more about how the documents of the Young Christian Workers were stored in the GDR and how did you finally get these boxes in Brussels? Were there any other documents that were confiscated and didn’t make it to the West?

N: We basically kept as few files as possible. At the time of my exemption I belonged to the oratory of St. Philipp Neri in Leipzig and there in the office in the parsonage the files were relatively safe. After the ban, I had the files briefly in Berlin with my Protestant colleague. As it turned out after 1990, he was a Stasi spy (informal collaborator). I cannot say with certainty whether he lost the file with the official letters with bishops and church authorities. For the whole of the years up to 1991, the files in Leipzig were hidden on the roof of the church. Once there was an action with Marlyse and others where I got the files to Brussels.

S: How did you personally experience the regime during your time with the Young Christian Workers? Did your work imply significant personal risks? Did you maintain contacts that were actually forbidden? With the West or the IYCW, for example?

N: When I took over the work, I broke off some personal letters to the West, I didn't want to deliver any “reports” for the Stasi. Until 1969 we had regular contact with the national management in Essen. Arnold Willibald's successor as national chaplain was a certain Höfels who brought us politically into play at meetings in the Federal Republic. That caused us to break off our contacts with the German national leadership. As a result, the contacts ran through individual people in Brussels. Berlin, where my parents lived, was a good opportunity to meet.

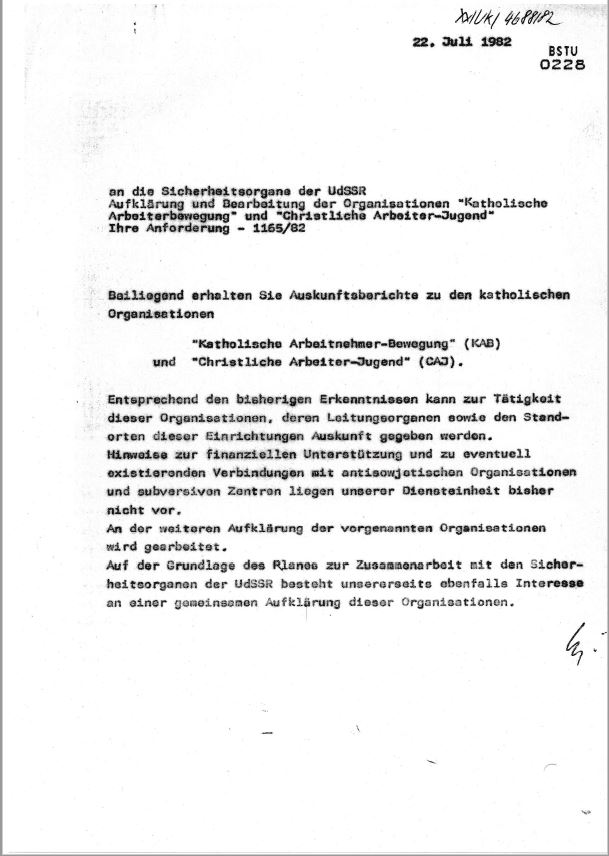

This report shows how the YCW was on the radar of the secret services

I only got direct contact with the State Security Service after the work was forbidden. I did what I recommended to the young people - not to be silent, but to tell everyone, then let them go. It was clear to me that after my time off work, I would face professional problems, and they kept coming back. I was even unemployed for a few weeks and had no chance to work as a hygienist in the health department, so I then worked as a nurse in psychiatry.

S: You were also responsible for initiatives to expand the CAJ to Eastern Europe. Can you tell me more about that? Were there major difficulties?

N: For example, when the Cardijn Foundation was founded, I only found out in 2000 that there was a YCW in Czechoslovakia before 1945 and that they were imprisoned after 1948. I then contacted them. We made first contacts through our summer camps and my predecessor Pastor Georg Kirch had already made contacts in Poland. There were YCW groups in Upper Silesia and I focused on Poland because I can speak the language. There were also contacts in Czechoslovakia, but then I was more likely to support people from the underground church who all knew the CAJ method. But in Czechoslovakia, the church was subject to massive controls.

Summer camp in the DDR with Pastor Georg Kirch in 1969

In Poland the church is a very clerical church, which is mainly expressed in sacramental and bombastic celebrations. Marcel Uylenbroeck wanted to support the cause and hoped to set the course through his friendship with the Krakow Archbishop Wojtyła. After a while, when I got his answer, he said there was no way for Poland. (I have to say that a pastor from an industrial city near Krakow told me that he could not convince his bishop either that a different pastoral care would be necessary. No wonder that he also negated the different realities as Pope) I had a lot of contacts in Poland. When the first groups of young people from small towns in Poland came to work in the GDR in 1970, I made contacts and tried to work with them in the spirit of the CAJ. But 90% of the young people were disinterested in what the church was. I was also followed by a Polish Stasi man and one of them even took over a workers' dormitory as head - because of me, as he told me.

In Upper Silesia, the YCW groups were trialed and then banned. It was found that these groups did not have the permission of the bishops. There were also discriminatory statements by priests about politically hostile tendencies at the YCW. The party secretary in the head of the group's operations and his brigadier protected them as much as possible and, for example, warned them when their apartment was bugged. My stay in Poland had to be reported when crossing the border.

A summer camp in south-east Poland with the Polish groups

S: One last question. According to you, what impact did existence under communism have on the YCW movement in general? Has that shaped today's movement (both nationally and internationally)?

N: In my opinion, when building a YCW in the countries, migrants who speak the national language should be included. Especially those whom we want to address are not necessarily those who speak English fluently.

English

English  Español

Español  Français

Français