Solidarity is a crucial idea within the IYCW and a quick glance at the archives reveals this. Throughout the years countless letters, bulletins and emails contains the words “in solidarity” instead of a more generic salutation. However, the IYCW also understood that solidarity is more than words alone. It has always encouraged solidarity through action, not only from national YCW’s to their compatriots, but also between various YCW’s around the globe. The many International Solidarity Campaigns coordinated by the International Secretariat are a result of a long tradition of solidarity. Although most were undertaken in support of the victims of dictatorships, military regimes and other forms of repression such as Apartheid, there was solidarity towards the victims of natural disasters as well. For this blog article, KADOC collaborated with the JOC d’Haiti in order to shed a light on how solidarity was turned from thought to practice.

One of the first responses of the IYCW to a natural disaster was after the 1960 Valdivia-earthquake in Chile, which is still the strongest earthquake ever recorded. The first detailed account of what happened reached the IYCW in the form of a letter written to Cardijn by Wim Verbakel, a Flemish Jocist who helped expand the YCW in Chile. He estimates that In the region south of Concepcion, around 40% of the homes were in ruins, as well as numerous other building such as factories and the YCW central. The magnitude of the earthquake was massive, for he also reports that the water level in several lakes had dropped around 10 meters and that five new volcanoes and several lakes had formed. Soon bound to leave for a voyage to Africa, Cardijn rapidly printed Verbakel’s account into a circular. He stated that there was only one response to this crisis: ‘a dry Sunday (without drinks and frivolities)’. In addition to fasting, members were encouraged to donate to Cardijn’s personal account with the mention ‘for Chile’. He himself had already pledged 10 000 franks.

Cardijn’s appeal for a ‘Dry Sunday’ in response to the 1960 Valdivia Earthquake

Cardijn’s appeal for a ‘Dry Sunday’ in response to the 1960 Valdivia Earthquake

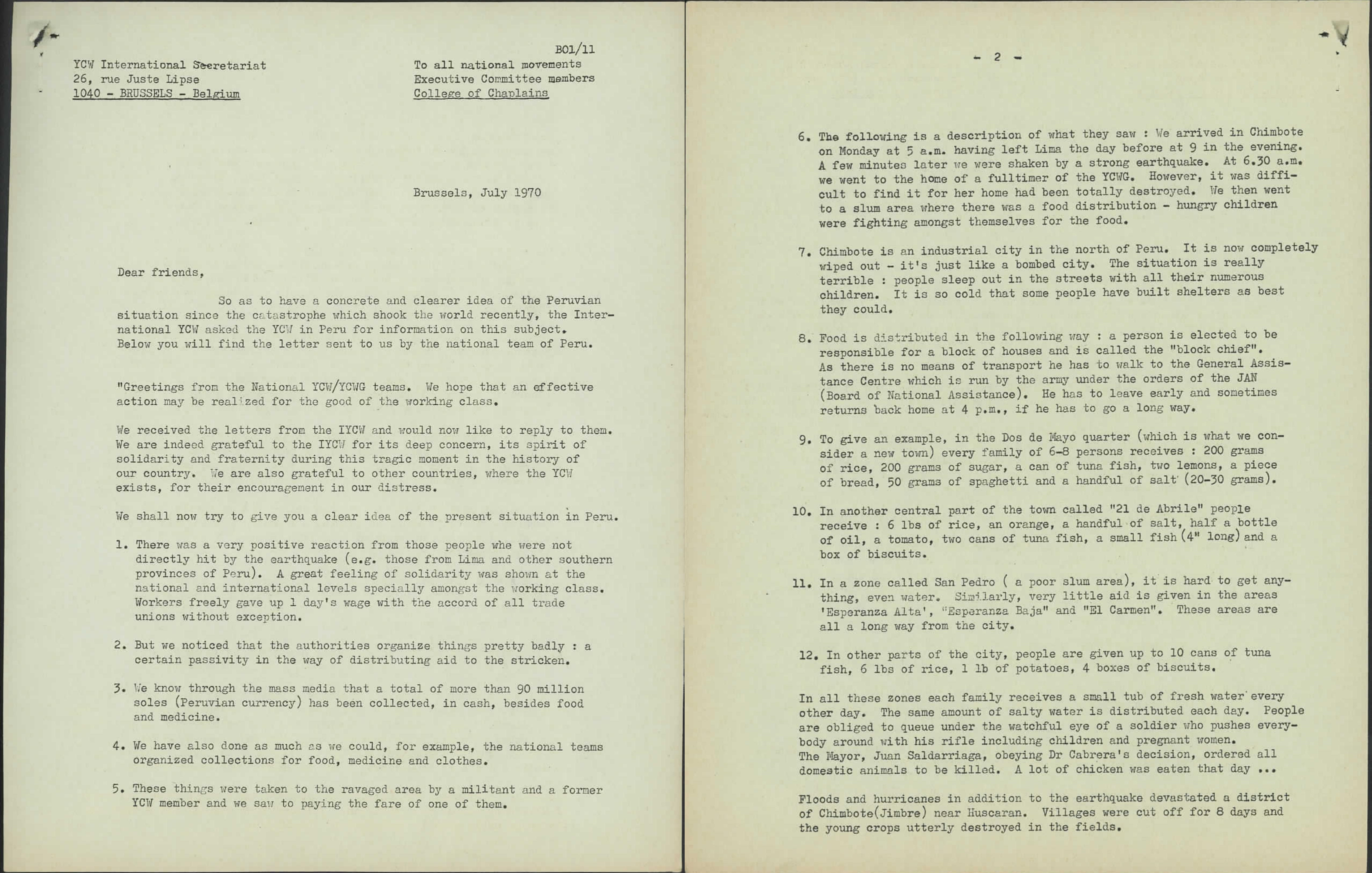

Scarcely ten years later, the earth again viciously trembled in South-America; his time near the coast of Peru. Buildings collapsed and massive landslides buried whole villages. 70 000 were dead, over 50 000 were injured and more than 3 million people were affected by the largest natural disaster in Peruvian history. Most factories, transport, schools and other services were either destroyed or came to a halt; the economic damage was unforeseeable. As had happened in 1960, the first step was always to gain information, not only about the disaster itself, but also about how it would impact young workers. JOC Peru provided a tragic overview of the situation. Many were homeless and basic necessities were scarce. Some places lacked fresh water and food rations were low everywhere. While Peru suffered intensely, the future was already rather grim; the disaster struck at a time when more than 450 000 people were unemployed and more than 180 000 young people were expected to find no job when leaving school. The International Secretariat made sure to translate the gripping account of JOC Peru in French and English and disperse it to all national YCW’s.

A circular of the IYCW containing a report on the earthquake in Peru

A circular of the IYCW containing a report on the earthquake in Peru

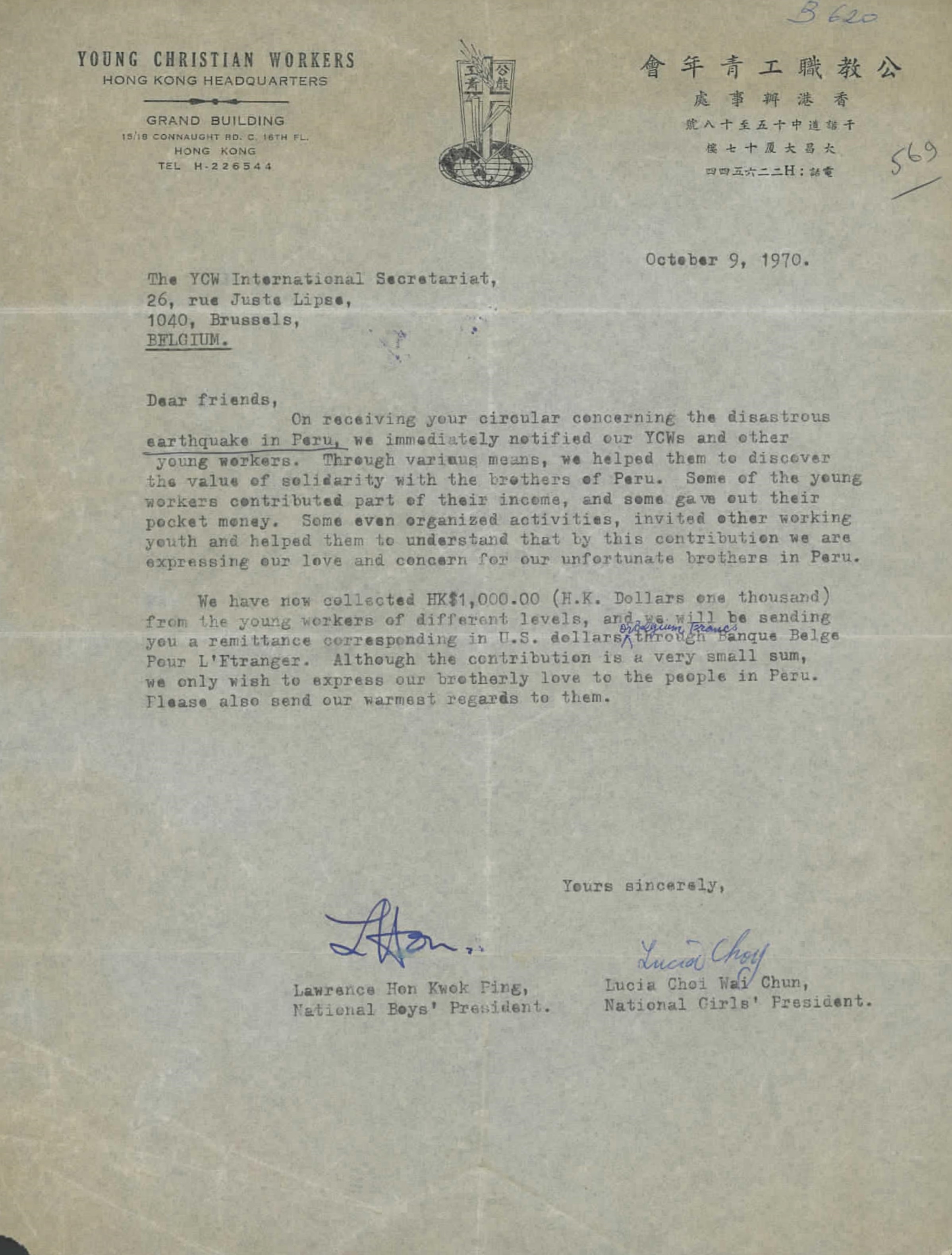

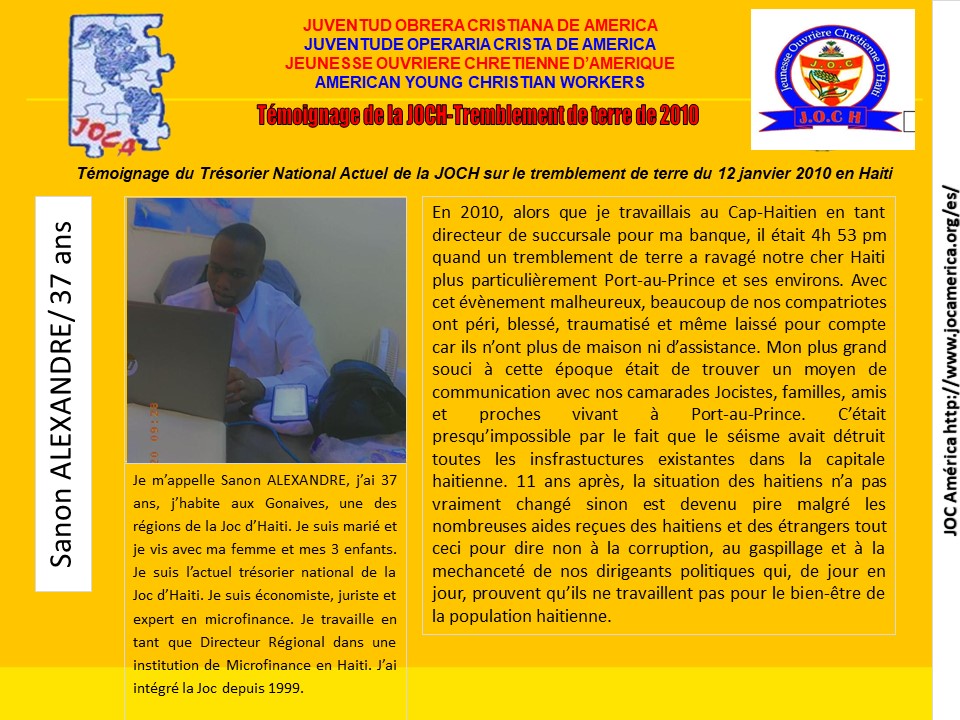

There was a problem however: there existed no IYCW solidarity-fund for natural disasters, only an international solidarity fund for Brazil opened fairly recently. For that reason, national YCW’s were, for the time being, asked to donate to government supported solidarity actions. Fortunately, not long after, in an kind act of solidarity with their neighbors, the Brazilian YCW allowed the IYCW to transfer $2000 from the existing IYCW solidarity fund for Brazil to Peru. Help also came from other parts of the world. The Hong Kong YCW for example, donated 1000 HK$, mostly pocket money or a part of the wages of young workers wanting to express their solidarity. A few months later, Bangladesh (then East-Pakistan) was ravaged by a cyclone causing more than 500 000 casualties. Here again, the IYCW gathered information first and then encouraged worldwide solidarity amongst young workers. In more recent times, the IYCW responded to the 1990 Luzon earthquake in the Philippines and the 2010 earthquake in Haiti. The Haitian YCW was happy to share their experience of the 2010 earthquake and searched for relevant documents. When on the 12th of January 2010 the earth trembled near the Haitian capital of Port-au-Prince, it quickly became clear that it was serious. Sanon Alexandre, today national treasurer of the Haitian YCW, recounts how he felt the earthquake when he was at work in Cap-Haitien. His first instinct was to find ways to communicate with fellow jocists, families and friends in Port-au-Prince. It was near impossible, he says, for Port-au-Prince was reduced to ruins. Sanon worked hard to gain information and sadly found out that several YCW members had not survived. He then found ways to report to the International Secretariat, which in turn informed their members around the world and started a financial aid campaign. Just as the letter from Wim Verbalen, Sanon’s story shows how for a large part the initial efforts of the Haitian YCW paved the way for an international response of the IYCW.

Help came from across the world and especially from Hong Kong, where militants donated from their own pocket money

Help came from across the world and especially from Hong Kong, where militants donated from their own pocket money

Although horrible, the experience with natural disasters helped to establish a strong tradition of international solidarity and shape a plan of action when disaster struck again. However, notwithstanding clear evolutions, the step from Cardijn’s personal bank account and a day ‘without frivolities’ to today’s International Solidarity Campaigns with a specific bank account was smaller than it seems. After all, the underlying idea and method of solidarity remained practically unchanged throughout. Technological change, which allowed for quicker news on the event, easier spreading of information and more efficient ways to gather funds, had brought the most noticeable changes. Whereas in 1970 news from Peru came slowly and the IYCW lacked a particular solidarity fund, in 2010 the IYCW informed its members about the situation and had already created specific bank account merely two weeks after the event.

Technology has a big impact on archives as well. The documents Sanon found for example, are what we call digital-born archives or, in other words, documents that have only ever existed digitally. They not only show that archives not only consists of that what is written and printed on paper, but also that the world is becoming increasingly digitized. Keeping up with this evolution is a key aspect of modern-day heritage conservation. Today, classifying your emails, Word-, PowerPoint- and Excel- documents is as important as classifying your paper-documents!

Sanon’s testimony made for our project is an excellent example of digital-born archives. Now it belongs to the heritage of the JOC d’Haiti.

Sanon’s testimony made for our project is an excellent example of digital-born archives. Now it belongs to the heritage of the JOC d’Haiti.

English

English  Español

Español  Français

Français